A Tale of Two Biopics: Maestro and Napoleon

Some thoughts on two potential awards contenders and what works for me on a biopic…

‘Tis the season for Oscar bait. And there’s no better genre that screams Oscar bait than the biopic. And, oh, lookee here, we have two opening theatrically this Thanksgiving week before they are released in streaming in December: Bradley Cooper’s Maestro (Netflix) and Ridley Scott’s two and a half-hour cut of the four-hour Napoleon (Apple TV+). They have to contend with the granddaddy of this year’s biopics, Christopher Nolan’s beyond masterly time-scrambling Oppenheimer. And although neither comes close, one of them is idiosyncratic enough to warrant a strong recommendation: Maestro.

Compression is the biggest challenge any filmmaker faces when bringing the life of a major historical character to the big screen. For me, the best biopics are those that focus on a specific chapter or aspect of that subject that will offer some insight into what made that person tick. Ava DuVernay’s Selma is a very good example: by centering Martin Luther King’s story on the events that led to the 1965 march to Selma, DuVernay and screenwriter Paul Webb not only gave us a portrait of a determined and flawed leader whose ideas were far more radical than the myth around him gives him credit for and the social, and political winds that threatened his fight towards securing equal voting rights for all African-Americans.

Knowing that it’s well nigh impossible to capture American composer and conductor Leonard Bernstein’s entire life and career, director, producer, actor and co-writer Bradley Cooper opts to focus on Bernstein’s relationship with his wife, the Costa Rican/Chilean actress Felicia Monteverde. While it’s true that his music seems to be shoved to the side throughout most of the film, we get enough of it in the soundtrack and reenactments to make us want to go out in search of those recordings. The attention to every single detail, from the clothes they actually wore, to their speech patterns and the use of the Bernstein home as a location, contributes to a world fully lived in and to the sense that we are a fly in the wall listening in. The end result is a sense of intimacy that serves as a counterpoint to the eloquent, vibrant, almost grandiose music Bernstein conducts and composes in the film.

Scott, on the other hand, like any old school epic filmmaker, aims for the big picture, a cliff notes version of history where he aims to reenact Napoleon Bonaparte’s most important while painting, with a big brush and much faux psychologizing, a broad portrait of the tactician, emperor and egotistical son of Corsica, actual history be damned. It’s too much for a two and a half hour film, which makes one wonder what the four-hour version that will stream on Apple TV+ right after its theatrical release will look like. One leaves a screening of Napoleon thinking that Sony, Apple TV+ and Scott made a mistake by releasing this version theatrically instead of the four-hour one. Had they done so, they could have marketed it as an actual movie event, intermission included.

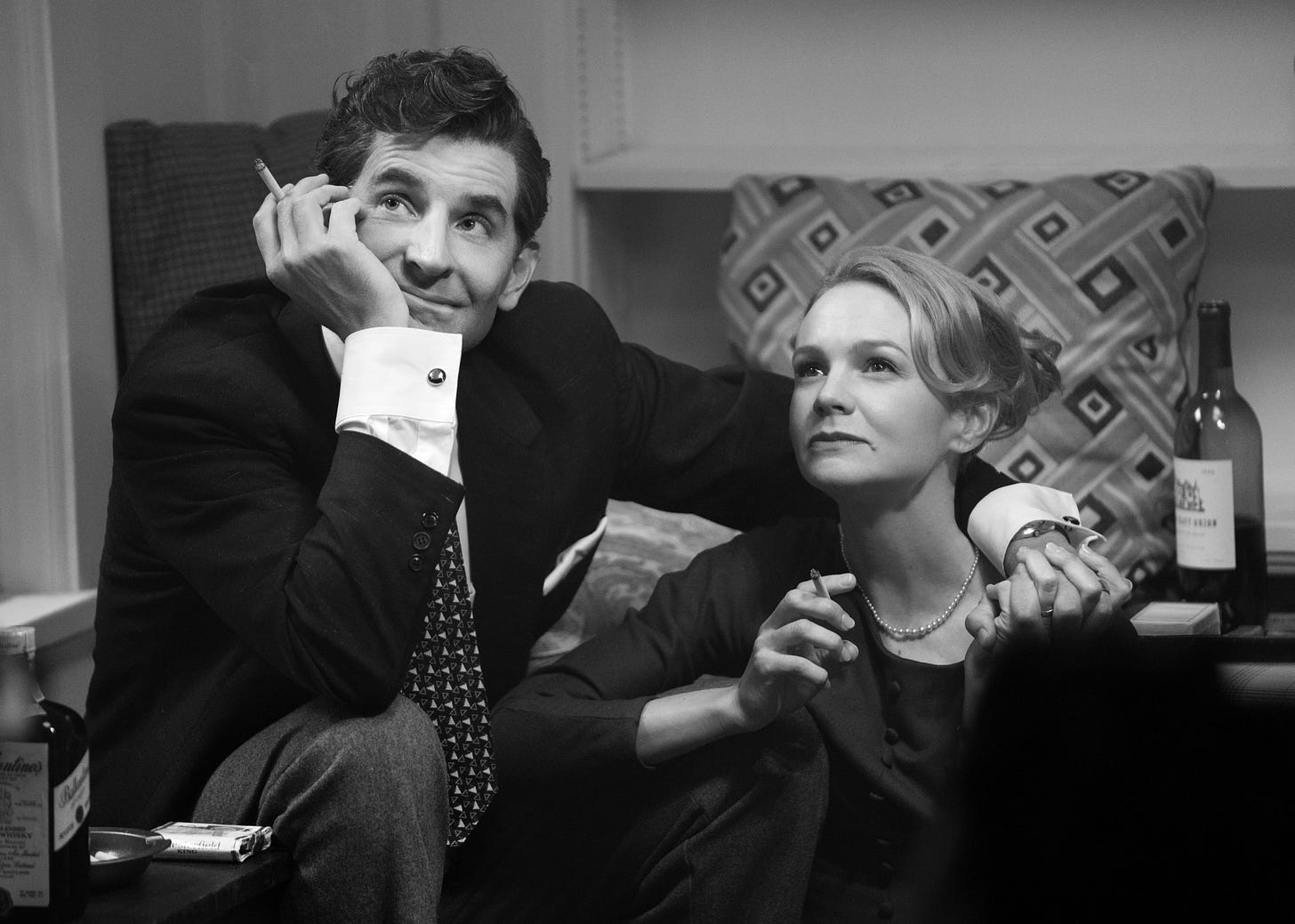

Cooper lays his cards on the table from the very first shot, when an elderly Bernstein is being filmed playing the piano at his home by a television crew and confesses to feeling a sense of solitude after his wife’s death. From there, Cooper splits the film in two with a technique that, by sheer serendipity, follows on the footsteps of Nolan’s Oppenheimer: sharp, almost expressionist black and white for Bernstein’s career ascent and his wooing of Felicia, and grainy, sometimes dirty color for the later years, all shot on Hollywood aspect ratio. The contrast between the two parts goes beyond the image; even the tone is different. The dialogue delivery in the black and white sequences is quick, almost rat-a-tat-ish, evoking the romantic comedies of the 1940s. These early scenes are exuberant, vivacious, from the moment Bernstein jumps out of bed, naked, nudging his male lover out of it after receiving the news that the New York Philharmonic’s conductor is ill and he needs to take over conducting duties without rehearsal on 1943, to his meeting Felicia at a party organized by his sister Shirley (a glorious Sarah Silverman) and the early years of their marriage and parenthood. The camera and the editing are fleet-footed, Matthew Libatique’s camera floating and gliding from room to room, from scene to scene in these early scenes. There is even a fantasy dance number as Bernstein takes Felicia to a rehearsal of Fancy Free, the ballet he choreographed for Jerome Robbins that later became the musical On the Town with Lenny himself suddenly taking on the role of one of the sailors

With the change to color comes a more measured pace as the strains in their marriage begin to show, especially as Felicia realizes that tolerating Leonard’s extramarital gay relationships as well as his overpowering persona is a difficult burden. Felicia can’t help but feel pushed aside by his fame, his liaisons and his own larger than life personality. Even her career seems to be at a standstill until she reaches that inevitable breaking point and reaffirms herself. And yet they are meant for each other. Cooper smartly recreates in full just one of Bernstein’s performances: his conducting Mahler’s Symphony No. 2 “Resurrection” with the London Symphony Orchestra at Ely Cathedral in 1973. Cooper captures Bernstein's sheer physicality, his joy, how music flowed through every extremity of his body and how he was able to transmit it back to his musicians. Cooper presents it as a love letter to Felicia, a reaffirmation of what made their relationship work and what drove his genius. It leaves you breathless and unprepared for what will follow: Felicia’s debilitating struggles with cancer, scenes that I at times found too hard to watch. My sister died of cancer two years ago and watching Mulligan recreate and personify the pain Felicia went through in her final days made me understand what my sister, and my parents who took care of her, went through.

The love story (if you can call it that) between Napoleon Bonaparte (Joaquin Phoenix) and Josephine de Beuaharnais (Vanessa Kirby) is one of the many plot strands Ridley Scott and screenwriter David Scarpa wrangle in Napoleon. They meet at a celebratory party after hundreds of prisoners jailed by Robespierre’s Reign of Terror are set free. She is somehow taken by his brashness and arrogance but it isn’t until her son pleads on her behalf for the return of his deceased father’s sword that something clicks between the future emperor of France and her. There’s a lot of bed play, teasing, letter writing, food fights, kinkiness and fits of jealousy as their courting ends in marriage. Unable to give him a child, Napoleon reluctantly divorces her and marries again. That capsule alone would have been enough for a two and a half hour movie in the vein of the many biopics made about European royalty, especially Henry VIII. But there is no chemistry between Phoenix and Kirby, with the British actress out-acting and out-smarting Phoenix in all of their scenes together.

But this is Napoleon Bonaparte, a man better known for his military accomplishments, huge ego and inferiority complexes than for bedroom intrigues. A man whose tentacles were felt all over Europe, particularly when he appointed his brother Joseph king of Spain which led to the Peninsular War (1907-1814) —itself, a perfect subject for an epic film. But I digress.

A film about Napoleon without a few good battle sequences would feel incomplete, and Scott gives us the entire kit and caboodle of Napoleon’s key victories and failures, from his triumph at Toulon vanquishing both the Spanish and English fleets to his ultimate defeat at Waterloo which, as staged in this cut, feels a tad anticlimactic. I do appreciate the anti-triumphalist tone of most of these battle sequence and its acknowledgement of the painful and brutal loss of human life in them, especially in the reenactment of the Battle of Austerlitz in 1805 where hundreds of soldiers from Austria and Russia perished as their bodies and horses sunk under the thin ice or were brutally slashed as they tried to resurface, part of the trap Napoleon set for them. I also cringed at Napoleon’s brutal repression of protesters on the streets of Paris by firing cannons on civilians. But they just happen without much consequence. Scott is too eager to get to the next battle sequence or the personal turmoil at home to care about such a thing. We rarely get any insight into how Napoleon devices these master plans, the debates around them, or how he felt about trampling those fellow citizens he was sworn to serve. Think, for example, of the many scenes where we see Queen Elizabeth I and her advisers stand around a giant floor map and discuss strategy in the two Cate Blanchett-starring Elizabeth films.

Granted, Bradley Cooper and his team have an advantage Scott and his team don’t have for Napoleon: hundreds of video and audio recordings that serve as a blueprint for how they will and did portray Leonard and Felicia Bernstein and their world. We expect some degree of accuracy in their performances. But when it comes to more historical figures like Napoleon, subject of hundreds if not thousands of books and articles and dozens of films, we do expect to see, if not an accurate representation of that figure, at least a complex interpretation of what drove him. And here is my biggest issue with the theatrical version of Napoleon: Joaquin Phoenix portrays him throughout the film as this arrogant, petulant, sometimes stern, man-child prone to temper tantrums. In other words, a direct descendant of his Emperor Commodus in Scott’s far more memorable and thrilling Gladiator (2000). It’s a one note performance that doesn’t do justice to such a historically complex figure.

Will the longer, streaming version solve any of these issues? Who knows. But Napoleon stands as another example as to why, when it comes to biopics of the epic kind, focusing on one aspect of your subject’s life is always a good idea, no matter how much you flip the bird at historical accuracy.